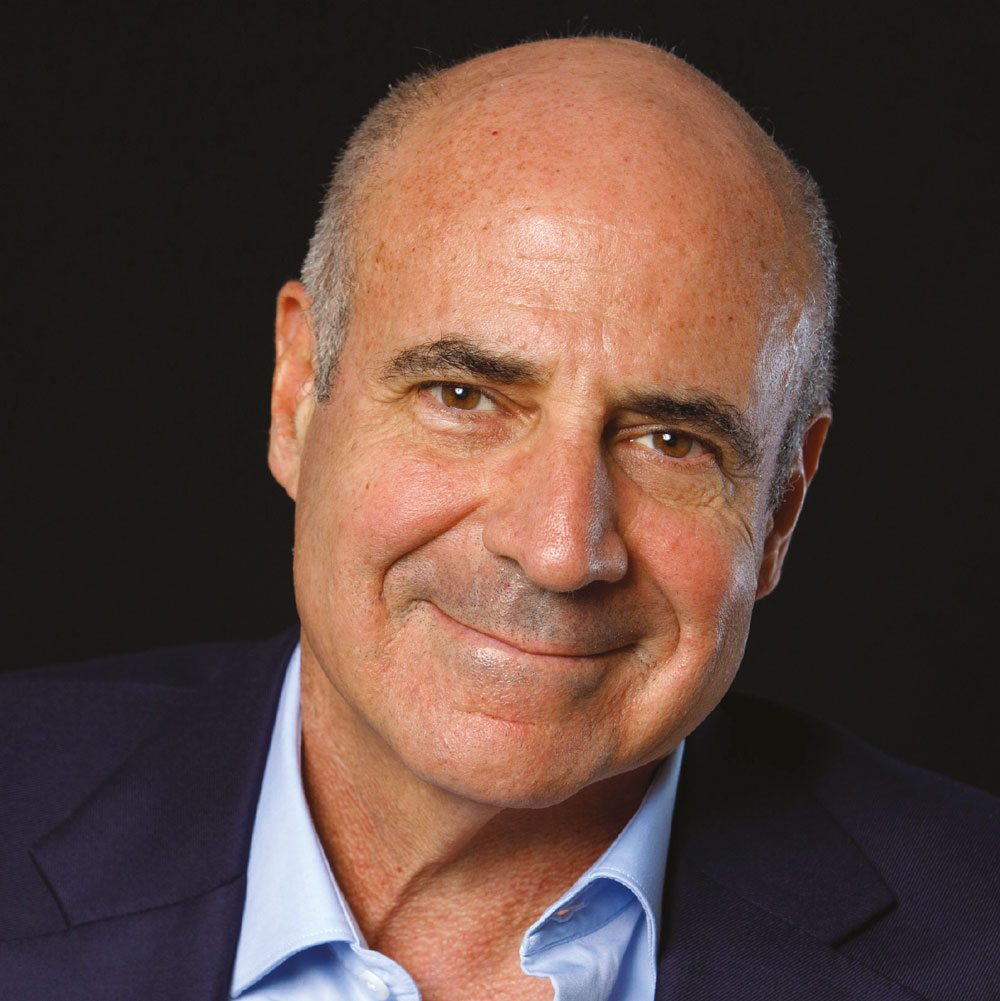

The financier and political activist talks about his new book Freezing Order and why Vladimir Putin wants him dead

Bill Browder is entitled to say, “I told you so!” because he did. For more than a decade. To anyone who would listen, and to plenty who wouldn’t. Browder spent years telling people that Vladimir Putin is the world’s most successful criminal. He would patiently explain how Putin’s money corrupted Russia and how Russian oligarchs in turn corrupted many other countries, including Britain. He wanted us to do something about the corruption. Mostly we didn’t, until it was too late.

When I first met Browder a few years ago, his first words to me (after a brief hello) were these: “Vladimir Putin is a crook. He’s like Pablo Escobar but with nukes. He’s the richest man in the world. He’s killing people in different countries, he’s killing people in his own country and getting away with it.”

Browder repeated the same speech to journalists, members of the US Congress, British and other European politicians, business groups, bankers, lawyers and anyone else within earshot. He did so at the risk of his life, family and personal fortune. With the world transfixed by Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, Browder’s view of Russia’s president is now mainstream – but rather than congratulating himself when we meet over lunch in London in late April, he seems more driven than ever.

“I spend a lot of time being really angry at the people who didn’t listen, because had they listened we could have avoided all this bloodshed and heartbreak that we’re currently experiencing,” he tells me, insisting that the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine was not the start of Putin’s war. He believes that war began back in 2007 with a cyberattack on Estonia, followed by the invasion of part of Georgia in 2008, then Crimea in 2014, plus horrific crimes in Syria and Chechnya, and the murders of opponents in London, Berlin and elsewhere.

“I think Putin’s actions [are] 95 per cent his fault but five per cent our fault. The 5 per cent our fault is that if we had been robust in responding to him for earlier atrocities he might have [made] a totally different calculation about what he was going to do in Ukraine. He was totally convinced that we were such a bunch of greedy bastards we would never come down hard on him if he went into Ukraine, because he had done so many other things that were so comparable. You know, invading Georgia was not that different — smaller country, less casualties, but the same thing. Basically, tearing up the UN charter, invading a sovereign state, killing people along the way.”

Browder is clear that Putin began the most risky gamble of his life when he initiated the first major land war between two European states since 1945, a move made not from strength but political weakness, including the Putin government’s poor record on coronavirus. (At least three quarters of a million Russians have died from the disease.) “His approval ratings were slumping… and he was terrified that covid would change the political landscape in Russia.”

Browder draws parallels with the turmoil, under-reported in the West, in Russia’s neighbour to the east, Kazakhstan. Putin “needed this invasion because he didn’t want to be overthrown by his people in the way that Nazarbayev got cleaned out in a weekend… I think he made the decision a long time ago. He understood that you can’t steal a trillion dollars from your own people… You can’t just do that and not expect that it’s going to come snapping back at you at some unexpected point.”

Browder is witty, sharp, likeable and – he admits – mulishly stubborn. American-born, married to a Russian woman, he’s now resident in Britain, and he’s been top of the Kremlin’s “Most Wanted” list for years. In the boom times after the Soviet Union collapsed he moved to Moscow and was once responsible for $4.5 billion invested through a hedge fund in Russian equities. He named it the Hermitage Fund, after one of Russia’s great treasures, the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg. At the time, Browder and other prominent business people thought Vladimir Putin might be good for the country. Who better than a tough ex-KGB colonel to clean up the Russian mafia and the endemic corruption in the Russian bureaucracy? “Yeah. I was cheering him in the first couple of years, thinking he seemed like an uncharismatic technocrat,” Browder remembers. “Russia needed a technocrat.”

But instead of cracking down on corruption, Putin took it over. From technocrat he became unchallenged leader of the Kremlin kleptocrats, the oligarchs who ensured Russia remains an under-developed country. It has eleven time zones and is rich in oil, gas and other resources, including the creativity of many of its 150 million people, but Russia has a GDP per capita less than a quarter that of the UK. The Russian economy is half the size of that of California. I tell Browder that Gary Kasparov, the Russian chess grand master, once told me: “all countries have a mafia. But in Russia, the mafia has a country.” Browder agrees but puts the same sentiment slightly differently: “Not all Russians are dirty, but all Russian oligarchs are dirty.”

Among those killed, arrested, jailed, and persecuted were Browder’s friends and business colleagues

One oligarch who opposed Putin back in February 2003 became an example of what not to do. Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the boss of Yukos, the biggest oil and gas producer in Russia, verbally attacked Putin live on Russian TV and challenged him to crack down on corruption. Khodorkovsky was then the richest and most powerful oligarch in Russia. Putin did nothing for a few months and then had Khodorkovsky arrested and put in a cage in a courtroom show-trial. The charges were all connected to corruption, the very crime Khodorkovsky complained about. Browder explained the importance of the show trial to me:

“Imagine you’re the seventeenth richest oligarch, you’re in the south of France on your yacht, parked off the hotel in Cap d’Antibes. You’ve just finished up in the bedroom with your mistress. You walk out to the living room, you flick on CNN, and there you see a guy far richer, far smarter, far more powerful than you, sitting in a cage. And so, one by one by one, these guys in the summer of 2004 went to Putin and said, ‘Vladimir, what do we have to do so we don’t sit in a cage?’ He said, it’s real simple. 50 per cent. Not 50 per cent for the Russian government or 50 per cent for the presidential administration of Russia. 50 per cent for Vladimir Putin. And at that moment in time, Putin became the richest man in the world and the number one oligarch in Russia.”

Once Browder himself began to take on Russia’s corrupt elite, the kleptocracy struck back. Among those killed, arrested, jailed, and persecuted were Browder’s friends and business colleagues. Putin’s political rivals, whom Browder met and admired, were also taken out. The charismatic Boris Nemtsov was murdered. The current opposition leader Alexander Navalny was poisoned and is now in jail. Navalny’s colleague Vladimir Kara-Murza was poisoned twice and is also now in jail. Browder says Putin’s increasing brutality and the crackdown on opponents are “not the actions of a man who is confident of his popularity.”

At the risk of spoiling our lunch, I ask Browder why he himself is still alive. He collapsed his Russian businesses, left Moscow, and dares not return, but Putin kept after him even when he moved to London. “I think that… the idea of killing a foreign critic on foreign soil, who is so well known…. might have been too much for even the [Putin] apologists. And I think his logic was, ‘OK, we hate Bill Browder, we want him dead. How do we make him dead without having to cross that Rubicon? Why don’t we arrest him, bring him back to Moscow, torture him until he makes some kind of confession that we want him to make and then feed him something in food so in a year he dies in jail?’”

When this plan failed either to destroy or discredit Browder, the Russian president appeared almost to suffer from Browder Derangement Syndrome. During his first summit with President Donald Trump in 2018 Putin name-checked Browder at the news conference, demanding Browder be extradited to Russia to face charges – inevitably – of tax evasion and corruption. The Kremlin obtained an Interpol Red Notice, a kind of international arrest warrant, but Browder dodged that bullet and the story – which reads like a thriller – led to his first bestselling book, Red Notice (2016). Browder’s latest book, Freezing Order (2022), takes up that David and Goliath struggle, and is also hitting the bestseller charts. It begins with Browder as a smart kid from the South Side of Chicago who had a strong belief that law-breaking should be punished. He was good with figures, graduated from Stanford Business School and went off to make his fortune in what western investors called “the Wild East” of post-Soviet Russia.

Another businessman of that same era once told me that, in the 1990s, survival in Russian business meant “we had three sets of (accountancy) books. One for the Russian government. One for the local mafia. And one for the real company accounts.” Taxes were paid to the Russian government, but other business expenses commonly included “taxes” – bribes – to officials and local criminals. Browder says he would not play that system because he “couldn’t accept that a small group of people could steal virtually everything from everybody and get away with it.” That meant he had to figure out how money was being stolen and then use Russian lawyers “to file lawsuits, launch proxy fights and brief government ministers on the damage this was doing to their country.” He used international media to publicise Russian corruption. All this brought what Browder calls “marginal change”, which nevertheless significantly pushed up the value of the investments he handled. Corruption, ultimately, is always bad for business. And yet Browder’s attempted clean-up plan had a downside: “Exposing corrupt oligarchs didn’t make me very popular in Russia. And in time my actions led to a cascade of disastrous consequences.”

Those disastrous consequences included damage to the lives of numerous friends, colleagues and business associates, and of course to Browder himself. Key personnel in his company and others who assisted him were harassed, jailed and worse. The most shocking example was the tax lawyer and auditor, Sergei Magnitsky. He worked for Browder uncovering the web of dodgy dealings, shell companies, corrupt officials and gangsters on a trail which led upwards to Putin’s inner circle. The Kremlin turned its fire on Magnitsky, who was bullied, threatened, and ordered to sign a “confession”. When that didn’t work, he was jailed, abused, beaten, denied proper medical care and ultimately murdered. That story makes one of the most moving – and sickening – chapters of Freezing Order.

Politicians, including in Britain, repeatedly refused to confront the reality of Putin’s Russia

Browder’s campaign could have collapsed at that point. He was accused not just of corruption but also of Magnitsky’s murder, and the murders of four other people. The idea that my lunch partner is a serial killer would be laughable if it wasn’t so dark and dangerous. They wanted him really badly. Fortunately, Browder’s profound stubbornness meant he continued his campaign, even when it seemed almost hopeless. The Obama administration wasn’t interested in tackling Russian corruption, but some in Congress began to listen. Eventually Congress passed the landmark Magnitsky Act in Sergei’s memory and in December 2012 Obama signed it into law. More than 30 other countries have followed suit, some more enthusiastically than others, cracking down on the corruptly-obtained assets of those Russians who could be identified through painstaking work by Browder and his associates. And yet Browder’s frustration, if anything, has grown. Despite all the evidence, all the suspicious “accidents” and “suicides” befalling enemies of Putin, all the money flowing into London, New York, the Caribbean, various banks, boutiques and jewellery stores from the south of France to New York, so many in the West for so long have been blinded by bling. Politicians, including in Britain, repeatedly refused to confront the reality of Putin’s Russia – or perhaps they knew that sordid reality but took the roubles anyway. You can buy the British establishment at bargain prices.

“People here are very inexpensive to corrupt,” Browder says. “It’s ridiculous how cheap the whole system is. For £50,000 or £75,000 people will do the most unbelievable things. And if you start offering millions, they will truly sell their soul. The Russians love that kind of stuff… they go everywhere with their bags of cash and just try it out on everybody and they have a high take-up rate here. I don’t know what it is about this country. Maybe [it’s] this weird colonial culture where everyone thinks everything is savage everywhere else and we’re all good here – and so Russia was just another one of these colonial places where gentlemen could make a bit of money and then head off to their gentlemen’s clubs and believe all is fine.”

Browder says £75,000 to a Russian oligarch is like a tip to a concierge. And he is particularly scathing about prime minister Boris Johnson’s close association with the Russian oligarch and now British newspaper owner Evgeny Lebedev, and his father, the former KGB officer, Alexander Lebedev. Uncharacteristically, Browder is almost lost for words when discussing why Johnson put the younger Lebedev in the House of Lords, the upper chamber of the British parliament, as “Lord Lebedev of Siberia”. And why would the man who was foreign secretary and is now Britain’s prime minister spend time at Lebedev’s social events at his home in Italy?

“I mean, that’s just the dumbest thing in the world. He has done such stupid stuff. Why go to parties? Why have Lebedev… a Russian who is the son of a KGB agent, and make them a lord? I mean, that’s just the dumbest… the effort you have to make to row back from that,” Browder sighs with exasperation. And as for Lebedev senior being a “former” KGB officer, Browder is equally dismissive: “Putin has said it – once KGB, always KGB.”

That leads us towards a consideration of what has changed since Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Even if western leaders have woken up to the dangers from Russian aggression, Browder predicts much worse is to come.

“Putin is going to continue to escalate much more than we can ever imagine or tolerate. Putin has been shown to be much weaker than we expected and [than] he expected to be. His entire persona is about projecting strength and fear, and he has failed in that. There’s no way he can recover that on a conventional basis. He’s not going to be able to fight the Ukrainians any better in the future than he has fought them in the past because, if anything, the Ukrainians are getting stronger.”

This means, Browder says, that Putin may eventually launch a nuclear strike. He points out that dropping two nuclear bombs on Japan brought an end to World War II. “We used nuclear weapons and all of sudden everybody gave up. I think he’s hoping that he wipes out a Ukrainian city of 600,000 people and [then] he looks at us and says, ‘You want another one?’ And then we say, ‘OK, let’s do a peace treaty. What do you need? Bulgaria and Romania?’ Whatever. I think that’s how it’s going to end up. Maybe not this week or this month. But that’s his ultimate play. The only thing that would prevent that is if it turns out the nuclear weapons are as ineffective as his army, and they blow up in his cellars.”

Much as I enjoy our conversation, I tell Browder he is failing to cheer me up. “There’s nothing cheerful about this,” he responds. “This is, at the moment, a desperate crisis. This guy is a psychopath.” I suggest that the West may retaliate for a nuclear strike by using nuclear weapons against Russia. Browder smiles and says wryly that Putin “understands that. It’s a very big thing to do. He’s a psychopath, but he’s not crazy.”

Browder’s latest book “Freezing Order” reads like a thriller and raises plenty of unanswered questions

Browder’s latest book, Freezing Order, like the earlier Red Notice, also reads like a thriller, and raises plenty of unanswered questions. How far do the Russians have kompromat – compromising material – on western leaders? What is the real relationship between Donald Trump and Putin or other Russians? How about Marine Le Pen, or Boris Johnson himself? What we do know is that the Trump team met with a key Kremlin lawyer to discuss the Magnitsky Act on 9 June 2016, during the height of the presidential election campaign, and that Browder is absolutely convinced Trump would get rid of the Magnitsky Act if he could. We also know the Russians offered to provide Trump with information on Hillary Clinton, and – according to one source in Browder’s book – “the Russians have been collecting videos of Trump with women since ’87.” Perhaps that content is best left to the imagination.

At least Browder retains his sense of humour. In one of the few laugh-out-loud sections of the book, Browder meets “Svetlana” at an event in Monaco. (Monaco’s Prince Albert, incidentally, makes a cameo appearance in the book as yet another powerful Friend of Putin.) Svetlana, described as a “hot blonde”, accidentally pushes into Browder at a hotel buffet. She tells Browder that she is “interested in fashion and human rights”. He moves away, but when she sees Browder handing out business cards to a couple of MPs, Svetlana asks for one too. Then she sends Browder late-night messages about how she feels a “strong connection” after their few minutes in the dinner queue. “William, are you still awake? I am. I can’t stop thinking about you. I’d really like to see you this evening.” Browder concludes: “I had to laugh. I’m a five-foot nine, middle-aged, bald man. Six-foot, busty, blonde models don’t throw themselves at me.”

Putin’s people have tried arresting Bill Browder, intimidating him, extraditing him, deluging him with vexatious lawsuits, and then unleashing Svetlana and the honeytrap. But Browder is still going. It’s simple, in a way. All he wants is truth, justice, and maybe – eventually – a better Russia. It’s difficult to be optimistic, but it is also unwise to underestimate Bill Browder.

2 Comments. Leave new

I had never heard of this man but not surprised our right wing newspapers are part of the problem in uk ..I am going to buy hi books and please god not the Welsh or the Scot’s but the bloody English will get rid of the curupt tortes boris Johnson and his cronies ,,one can only live in hope

I believe that Putin.s war in Ukraine started in 1945 at the end of the second world war when Churchill and Roosevelt made plans to invade Russia as it was believed at that time that Russia was weakened by the war and would be easy pickings. For some reason that I could never fathom there was a viscreal hatred of the Russian people. The west at that time was mostly facist especially the churches which abhorred communism. This then led to the cold war followed Disney land NATO Threatening Russia for the past number of years as everytime the Russian troops moved out of the west NATO forces moved in, as in Germany Poland Hungary the Baltic States etc. End