Earl Mountbatten: Re-evaluating the legacy of one of the last century’s most controversial leaders

Earl Mountbatten

The murder on 27 August 1979 of Earl Mountbatten of Burma, better known as Dickie Mountbatten, which forms the first episode of the current series of The Crown, made news headlines around the world. As one obituary noted, “It seemed almost unbelievable that one human being could have touched the history of our century at so many points.” Head of Combined Operations when he became the youngest Vice-Admiral since Nelson, a member of the Chiefs of Staff, the only British World War II Supreme Allied Commander, the last Viceroy and first Governor-General of India, First Sea Lord and Chief of the Defence Staff and that is before his Royal connections are even mentioned.

A great-grandchild of Queen Victoria and her last godchild; a close friend of Edward VIII, who was his best man; the match-maker between the future Queen Elizabeth ll and his nephew Prince Philip, who on naturalisation took the Mountbatten name; the “honorary grandpapa” and probably the single greatest influence on Prince Charles and the most successful member of the Royal Family to combine ceremonial duties with a career.

Ten days after his death his funeral took place at Westminster Abbey with 1,400 guests including the Queen, the Duke of Edinburgh, the Prince of Wales, most of the crowned heads of Europe, the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, and four of her predecessors. It was watched by a crowd of over 50,000 spectators and televised in over twenty countries. Further services took place throughout the world and a memorial service with 2,000 people followed in December with the Prince of Wales again giving the address.

However, in spite of trying to curate his reputation and legacy with carefully controlled books, articles and television programmes, Mountbatten had been a controversial figure even during his lifetime. Was he one of the outstanding leaders of his generation, or a man over-promoted because of his royal birth, high-level connections, film-star looks and ruthless self-promotion?

What was the true story behind controversies such as the 1942 Dieppe Raid and Indian Partition? To a naval colleague he was: “A single-minded enthusiast in anything he took up and endowed with boundless energy and ability, I am sure that no one in the Fleet, even in those early days, doubted that he would go right to the top and deservedly so on his own merits.” However the historian David Cannadine thought “there was about almost everything Mountbattten did an element of the makeshift, the insubstantial, the incomplete, and the disingenuous, a disquieting gap between the promise and the performance that no amount of bravura on his part could ever quite conceal.”

The record is certainly mixed. His first command, HMS Kelly, spent more time in repairs than action and yet he turned his various debacles into successes and was awarded a Distinguished Service Order (after lobbying King George Vl) when some of his fellow officers wanted him court martialed. Of the 6,000 soldiers and commandos who took part in the Dieppe Raid, over 900 were killed, 586 wounded and almost 2,000 captured, with the Royal Regiment of Canada suffering 97% casualties in under four hours. It was Mountbatten, as Chief of Combined Operations, who had ostensibly been in charge of the attack and who had given the orders to remount it after it had been cancelled and, yet, his career suffered no setback. Instead it was the Force Commander Major-General “Ham” Roberts who found himself demoted to running a recruiting depot.

As Supreme Allied Commander South East Asia, a political as much as military appointment, Mountbatten fell out with his generals, found himself caught between the competing demands of the Americans and Chinese in a confused command structure and, starved of resources by Churchill, was forced to abandon most of his military plans. And yet he restored morale to the “Forgotten” 14th Army and drove the Japanese out of Burma.

The rapid transfer of power, Indian Partition, the subsequent violence and problems in Kashmir continue to be debated. On the criteria set for him on going out as Viceroy – unitary Government by June 1948, “fair and just arrangements” for the Princes, “the closest cooperation with the Indians” and no “break in the continuity of the Indian Army” – he failed. But faced with the instability of the Interim Government, the breakdown in British administration, the Indian impatience for independence and rising communal violence, Mountbatten had little choice. Rushing partition was tactical – to concentrate minds, demonstrate good faith and narrow options – but also if he had not rushed it, there would have been no power to hand over. His brief had been to hand over power with as much dignity as possible from a British government with other priorities – and on that basis he had succeeded.

Mountbatten was a man full of contradictions. Self-confident in public life, he was insecure when it came to his marriage, which was bedevilled with infidelities on both sides. Able to think outside the box and see the big picture, he was obsessed with trivial detail – often to do with his own personal appearance or prestige. As his former Military Assistant, Pat MacLellan, noted “He never actually fitted in. He didn’t play by the same rules as other naval officers. Above all he wanted to be accepted. How to prove you’re better than everyone else is by getting to the top.”

But a dark secret threatened that very ambition. Mountbatten was bisexual at a time when homosexuality was an offence and service officers who were known to be gay would be dismissed. At any time during his fifty-year service career he could have lost everything. He was not only bisexual – a fact accepted by numerous colleagues and superiors and therefore protected – but also a paedophile, described in one FBI file as “a homosexual with a perversion for young boys”. Only now, forty years after his death, do his victims feel able to come forward to speak about their abuse.

In 1980 Pat MacLellan wrote: “The interesting biography will be the one that is published in 30 or 40 years’ time when the dust has settled.” The time for that re-evaluation has come.

Andrew Lownie is the author of The Sunday Times best seller, The Mountbattens: Their Lives and Loves

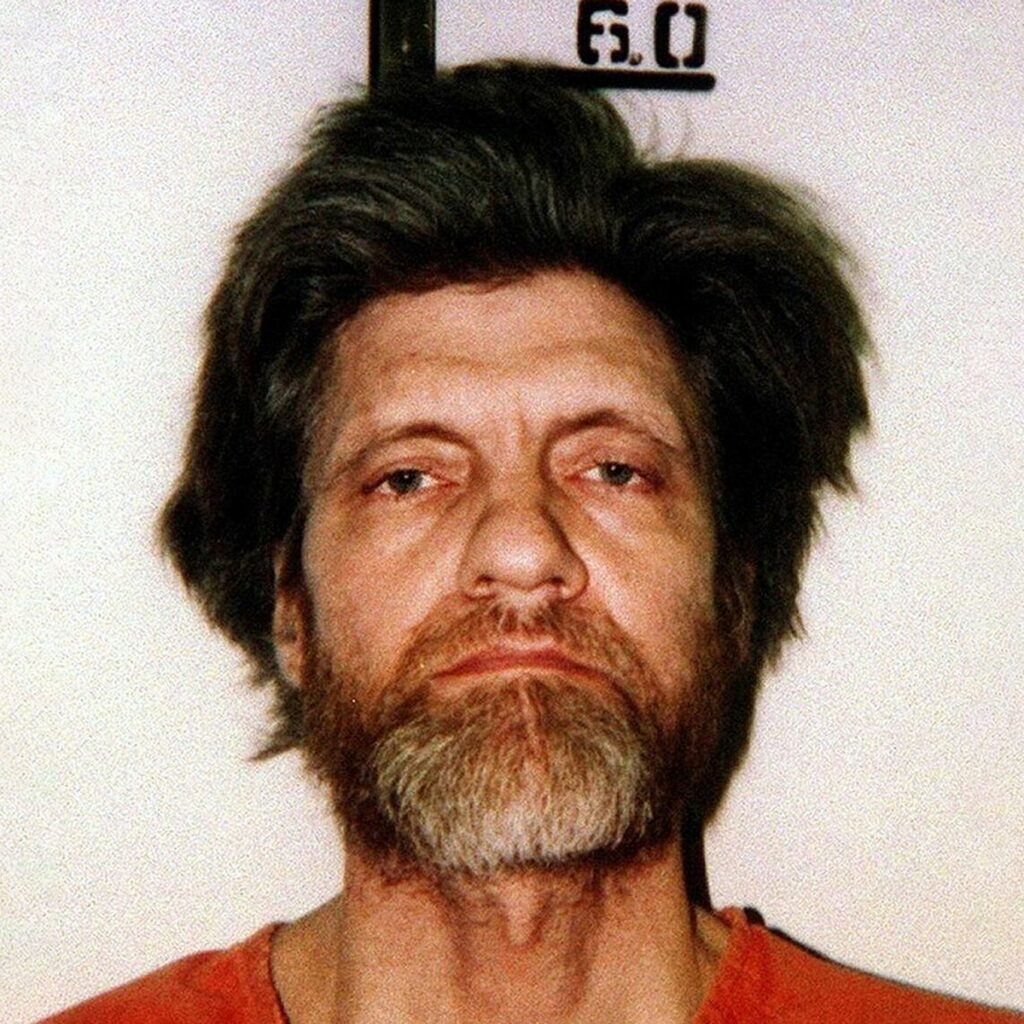

Ted Kaczynski

Your email address will not be published. The views expressed in the comments below are not those of Perspective. We encourage healthy debate, but racist, misogynistic, homophobic and other types of hateful comments will not be published.

1 Comment. Leave new

Not a great man but a great poster. Margot Asquith’s description of Kitchener seems to fit Mountbatten equally well. He was incredibly handsome and charismatic, and full of energy, but his record of achievement as suggested here is much more mixed. He probably deserves a mulligan on Indian independence. There was really no alternative to the partition of India and partition was never going to be achieved without a huge amount of what we call today ethnic cleansing. The same tolerance cannot be extended to the Dieppe Raid which was obviously a fiasco in the making for which he bears primary responsibility. Likewise his performance in SE Asia where Alan Brooke, an acerbic but usually accurate commentator, dismissed him as a principal boy in a pantomime. And far from restoring morale in the 14th army he faced the threat of the resignation of almost the entire officer corps when he supported the firing of Bill Slim as its Commander. This turned into another fiasco where he was able to dump the blame on some else. His postwar record at the Admiralty is also somewhat checkered although this was a period when Britain’s imperial pretensions, which survived into the 1960’s, collapsed so perhaps he was displaying some realism. It’s hard to believe he had the respect of his fellow brass hats when Sir Gerald Templer the much admired CIGS told him he was so crooked that if he swallowed a nail he would pass a corkscrew (Templer was more graphic).

Then there is the matter of his sexuality which was obviously widely known in British governing circles and by the Royal family. His wife’s conduct in the context of the times was also totally scandalous. He was obviously protected as were many other leading members of the British upper classes. No hint of any of his private life ever found its way into the press even though he had sworn enemies among its ownership notably Lord Beaverbrook who was particularly incensed by Canadian casualties at Dieppe. Given 21st century mores one is perhaps inclined to be more tolerant here but it’s hard to ignore the fact that plenty of people were being banged up, or committing suicide as happened with poor Turing, while massive hypocrisy was protecting Mountbatten’s behavior which apparently extended to the abuse of young boys. Perhaps this protection was necessary in the 30’s to preserve the cohesion of British society in the face of the challenge from Germany and Japan but his promotions given his record and private life cannot help but raise eyebrows even today.

Among the great and good it’s hard to escape the fact that he was a fail.